Irvine artist paints sights of Cuba

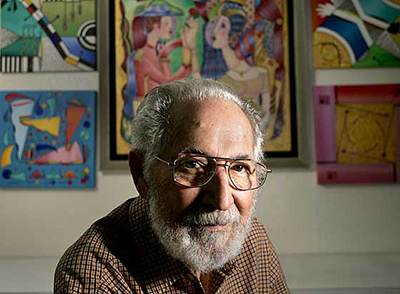

Viredo, exiled Cuban artist, to show at John Wayne Airport

By ERIN CARLYLE / The Orange County Register

It's been 40 years since Viredo Espinosa fled Cuba, but the vibrant colors and traditions of his homeland are as fresh in his memory as if he left yesterday.

From his home studio in Irvine, the 79-year-old artist depicts in rich, bright oil paint the festivals, legends, and religious symbols of his beloved Cuba. His canvases convey a blend of joyful memories and sorrowful regret that the Cuba of his youth is no more.

Growing up in the port town of Regla across the bay from Havana, Viredo, as he is known professionally, was surrounded by the descendants of slaves who worked in the harbor and practiced the religious traditions their forefathers carried from Africa. There were the abaku, an elite secret male society from the Calabar region of West Africa; those who practiced palo monte, areligion from Central Africa; and the lukum,as the Nigerian Yoruba are known in Cuba,who practicedsanter a, a blend of Catholicism and Yoruba religion.

As a child, Viredo and his friends trailed in the wake of Yoruba offerings. "They would offer a fountain of food to the gods," he said, "and we would come along and eat it!" He spent afternoons clambering onto ships docked at the harbor, jumping off into the bay. "I swam like a fish," he recalled, his eyes sparkling.

Viredo came to the United States in 1969. But Cuba - at least the Cuba before Fidel Castro - still feels like home.

Viredo's sweet memories of his native country shine through in a group of 14 works to be displayed at John Wayne Airport July 23 through the end of August. Last year, the airport's Arts Commission selected Viredo to show in the public art space, near the security line and baggage claim areas.

In "Shangrila Tropical,"Viredo evokes images recalling the paradise that Cuba once was. There is a bright orange and red road, a brilliant sun, and snails - yellow, pink, orange. "There are all colors," Viredo explained, "except blue."

According to legend of the tanos, the native people of Cuba, a man asked the deity for a blue snail to give to his girlfriend. The deity said he could offer a snail of any color other than blue - because blue was where he dwelled.

"God's spirit was blue," Viredo said.

Another painting, "Colores Habaneros,"recalls the cenefas, or decorative borders, that Viredo observed painted and tiled onto the walls of Cuban houses. Colors and symbols dance across the canvas of "The Cabildo is Coming,"a depiction of an Afro-Cuban religious parade in his hometown.

In Havana during the late 1940s and early 1950s, Viredo was a member of Los Once, or "The Eleven," an avant-garde group of young artists who brought new techniques to a country where the traditional realism of the academy still prevailed.

"The group of Los Oncehas been one of the most important Cuban art groups in the 20th-century Cuban art," said Adolfo Nodal, president of the Los Angeles cultural affairs commission and an expert in Cuban art.

Stylistically diverse, Los Onceexhibited together a handful of times and gained their moniker from a critic.

"They are an example of diversity," said Gregorio Luke, former director of the Museum of Latin American Art in

Long Beach. "They're young, they're different, and they tried to multiply the ways of being Cuban."

In Havana, Viredo and other artists congregated at Las Antillas Caf, talking about the artistic movements - cubism, abstract expressionism - they'd seen abroad.

Viredo's career began to take off, as he exhibited and sold paintings, then gained commissions to paint murals.

But when Castro took over the country in 1959, artists were pressured to join a national arts association and sign an accompanying political statement. Joining was necessary to access artist materials and exhibit.

Those who joined flourished and gained prominent artistic positions. Viredo's friends urged him to join, but he refused, effectively ending his artistic career in Cuba.

During the next few years, the artist obtained occasional commercial work. But in 1965, Viredo and his wife decided to leave.

To gain his freedom, he had to work for three and a half years cutting sugar cane. At one point, he was separated from Alicia, whom he'd married in 1955, for eight months.

When the time came to leave, the couple had to leave everything behind but the clothing they wore.

"You had to wear a suit and tie," Viredo said. "Know why? They wanted to give the impression that the people who lived [in Cuba]were rich."

The couple flew into Miami, then to Los Angeles where they could stay with friends. Viredo found commercial work, at a sign company and sketching merchandise for print ads of the May Company department store.

"What I liked was that at least I was working," he says, laughing.

The artist worked in commercial art for 15 years. But on Saturdays and Sundays, he painted his fine art, always in natural light.

"He had to work many years to begin to be recognized here," Nodal said. "What is undeniable is the man's courage, independence, insistence, to continue to paint.

In 1977, Viredo began devoting himself fully to his art. He created a mural in Long Beach and has shown at several Orange County galleries, including his own space in Santa Ana's Santora Building. The couple moved to Irvine 16 years ago.

"He's a very high-quality artist," Nodal said. "But he suffers from what many Cuban refugee artists suffer from," Nodal said. "He left Cuba, was against the government, sort of got blacklisted by the Cuban government, and wiped out of the history of Cuban art."

Viredo's situation is typical for artists who left Cuba from the 1950s to the 1990s, Nodal said. The Cuban exile community, he added, was too busy "fighting Fidel" to turn its focus to supporting Cuban artists.

"He's never had the success that he's due," Nodal said.

Viredo acknowledges he'd like to see more of his paintings exhibited in Cuba. But rather than answer questions about what he's accomplished and would still like to do as an artist, Viredo turns to the personal.

"The best thing is to have a good wife," he said. "Because this gives you merit, influence, so that you can keep painting."